Executive Summary

Report of a Committee of Privy Counsellors

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 6 July 2016

HC 264

© Crown copyright 2016

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where

otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/

version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or

email: [email protected].

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the

copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at

[email protected]

Print ISBN 9781474133319

Web ISBN 9781474133326

ID 23051602 46561 07/16

Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum

Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Contents

Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4

Pre‑conflict strategy and planning .................................................................................... 5

The UK decision to support US military action ................................................................. 6

UK policy before 9/11 ................................................................................................. 6

The impact of 9/11 ................................................................................................... 10

Decision to take the UN route .................................................................................. 16

Negotiation of resolution 1441 ................................................................................. 19

The prospect of military action ................................................................................. 21

The gap between the Permanent Members of the Security Council widens ........... 24

The end of the UN route .......................................................................................... 30

Why Iraq? Why now? ..................................................................................................... 40

Was Iraq a serious or imminent threat? ................................................................... 40

The predicted increase in the threat to the UK as a result of military action in Iraq. 47

The UK’s relationship with the US.................................................................................. 51

Decision‑making ............................................................................................................ 54

Collective responsibility ........................................................................................... 55

Advice on the legal basis for military action ................................................................... 62

The timing of Lord Goldsmith’s advice on the interpretation of resolution 1441 ...... 63

Lord Goldsmith’s advice of 7 March 2003 ............................................................... 65

Lord Goldsmith’s arrival at a “better view” ............................................................... 66

The exchange of letters on 14 and 15 March 2003 ................................................. 66

Lord Goldsmith’s Written Answer of 17 March 2003 ................................................ 67

Cabinet, 17 March 2003 .......................................................................................... 68

Weapons of mass destruction ........................................................................................ 69

Iraq WMD assessments, pre‑July 2002 ................................................................... 69

Iraq WMD assessments, July to September 2002................................................... 72

Iraq WMD assessments, October 2002 to March 2003 ........................................... 75

The search for WMD................................................................................................ 77

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

2

Planning for a post‑Saddam Hussein Iraq ..................................................................... 78

The failure to plan or prepare for known risks ......................................................... 78

The planning process and decision‑making ............................................................ 81

The post‑conflict period .................................................................................................. 86

Occupation ............................................................................................................... 86

Looting in Basra ................................................................................................ 86

Looting in Baghdad .......................................................................................... 88

UK influence on post‑invasion strategy: resolution 1483 .................................. 89

UK influence on the Coalition Provisional Authority .......................................... 90

A decline in security........................................................................................... 93

The turning point ............................................................................................... 96

Transition ................................................................................................................. 97

UK influence on US strategy post‑CPA ............................................................. 97

Planning for withdrawal ..................................................................................... 97

The impact of Afghanistan ................................................................................. 99

Iraqiisation ....................................................................................................... 101

Preparation for withdrawal ..................................................................................... 103

A major divergence in strategy ........................................................................ 103

A possible civil war .......................................................................................... 104

Force Level Review ......................................................................................... 107

The beginning of the end................................................................................. 108

Did the UK achieve its objectives in Iraq? .................................................................... 109

Key findings ..................................................................................................................111

Development of UK strategy and options, 9/11 to early January 2002 ...................111

Development of UK strategy and options, January to April 2002 – “axis of evil” to

Crawford .................................................................................................................111

Development of UK strategy and options, April to July 2002 ................................. 112

Development of UK strategy and options, late July to 14 September 2002 .......... 112

Development of UK strategy and options, September to November 2002 – the

negotiation of resolution 1441................................................................................ 113

Development of UK strategy and options, November 2002 to January 2003 ........ 113

Development of UK strategy and options, 1 February to 7 March 2003 ................ 114

Iraq WMD assessments, pre‑July 2002 ................................................................. 115

Iraq WMD assessments, July to September 2002................................................. 116

Iraq WMD assessments, October 2002 to March 2003 ......................................... 117

The search for WMD.............................................................................................. 117

Executive Summary

3

Advice on the legal basis for military action, November 2002 to March 2003 ....... 119

Development of the military options for an invasion of Iraq ................................... 120

Military planning for the invasion, January to March 2003..................................... 121

Military equipment (pre‑conflict)............................................................................. 122

Planning for a post‑Saddam Hussein Iraq ............................................................. 122

The invasion .......................................................................................................... 123

The post‑conflict period ......................................................................................... 123

Reconstruction ....................................................................................................... 124

De‑Ba’athification ................................................................................................... 125

Security Sector Reform .......................................................................................... 125

Resources .............................................................................................................. 126

Military equipment (post‑conflict) ........................................................................... 126

Civilian personnel .................................................................................................. 127

Service Personnel .................................................................................................. 127

Civilian casualties .................................................................................................. 128

Lessons ........................................................................................................................ 129

The decision to go to war....................................................................................... 129

Weapons of mass destruction ............................................................................... 130

The invasion of Iraq ............................................................................................... 133

The post‑conflict period ......................................................................................... 134

Reconstruction ....................................................................................................... 135

De‑Ba’athification ................................................................................................... 137

Security Sector Reform .......................................................................................... 138

Resources .............................................................................................................. 138

Military equipment (post‑conflict) ........................................................................... 139

Civilian personnel .................................................................................................. 140

Timeline of events ........................................................................................................ 141

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

4

Introduction

1. In 2003, for the first time since the Second World War, the United Kingdom took part

in an opposed invasion and full‑scale occupation of a sovereign State – Iraq. Cabinet

decided on 17 March to join the US‑led invasion of Iraq, assuming there was no

last‑minute capitulation by Saddam Hussein. That decision was ratified by Parliament

the next day and implemented the night after that.

2. Until 28 June 2004, the UK was a joint Occupying Power in Iraq. For the next five

years, UK forces remained in Iraq with responsibility for security in the South‑East; and

the UK sought to assist with stabilisation and reconstruction.

3. The consequences of the invasion and of the conflict within Iraq which followed are still

being felt in Iraq and the wider Middle East, as well as in the UK. It left families bereaved

and many individuals wounded, mentally as well as physically. After harsh deprivation

under Saddam Hussein’s regime, the Iraqi people suffered further years of violence.

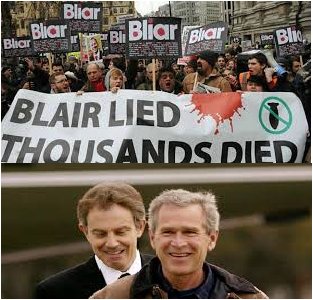

4. The decision to use force – a very serious decision for any government to take –

provoked profound controversy in relation to Iraq and became even more controversial

when it was subsequently found that Iraq’s programmes to develop and produce

chemical, biological and nuclear weapons had been dismantled. It continues to shape

debates on national security policy and the circumstances in which to intervene.

5. Although the Coalition had achieved the removal of a brutal regime which had

defied the United Nations and which was seen as a threat to peace and security, it

failed to achieve the goals it had set for a new Iraq. Faced with serious disorder in Iraq,

aggravated by sectarian differences, the US and UK struggled to contain the situation.

The lack of security impeded political, social and economic reconstruction.

6. The Inquiry’s report sets out in detail decision‑making in the UK Government covering

the period from when the possibility of military action first arose in 2001 to the departure

of UK troops in 2009. It covers many different aspects of policy and its delivery.

7. In this Executive Summary the Inquiry sets out its conclusions on a number of issues

that have been central to the controversies surrounding Iraq. In addition to the factors

that shaped the decision to take military action in March 2003 without support for an

authorising resolution in the UN Security Council, they are: the assessments of Iraqi

WMD capabilities by the intelligence community prior to the invasion (including their

presentation in the September 2002 dossier); advice on whether military action would be

legal; the lack of adequate preparation for the post‑conflict period and the consequent

struggle to cope with the deteriorating security situation in Iraq after the invasion.

This Summary also contains the Inquiry’s key findings and a compilation of lessons, from

the conclusions of individual Sections of the report.

8. Other Sections of the report contain detailed accounts of the relevant decisions and

events, and the Inquiry’s full conclusions and lessons.

Executive Summary

5

9. The following are extracts from the main body of the Report covering some of the

most important issues considered by the Inquiry.

Pre‑conflict strategy and planning

10. After the attacks on the US on 11 September 2001 and the fall of the Taliban regime

in Afghanistan in November, the US Administration turned its attention to regime change

in Iraq as part of the second phase of what it called the Global War on Terror.

11. The UK Government sought to influence the decisions of the US Administration and

avoid unilateral US military action on Iraq by offering partnership to the US and seeking

to build international support for the position that Iraq was a threat with which it was

necessary to deal.

12. In Mr Blair’s view, the decision to stand “shoulder to shoulder” with the US was an

essential demonstration of solidarity with the UK’s principal ally as well as being in the

UK’s long‑term national interests.

13. To do so required the UK to reconcile its objective of disarming Iraq, if possible

by peaceful means, with the US goal of regime change. That was achieved by the

development of an ultimatum strategy threatening the use of force if Saddam Hussein

did not comply with the demands of the international community, and by seeking to

persuade the US to adopt that strategy and pursue it through the UN.

14. President Bush’s decision, in September 2002, to challenge the UN to deal with

Iraq, and the subsequent successful negotiation of resolution 1441 giving Iraq a final

opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations or face serious consequences

if it did not, was perceived to be a major success for Mr Blair’s strategy and his influence

on President Bush.

15. But US willingness to act through the UN was limited. Following the Iraqi declaration

of 7 December 2002, the UK perceived that President Bush had decided that the US

would take military action in early 2003 if Saddam Hussein had not been disarmed and

was still in power.

16. The timing of military action was entirely driven by the US Administration.

17. At the end of January 2003, Mr Blair accepted the US timetable for military action

by mid‑March. President Bush agreed to support a second resolution to help Mr Blair.

18. The UK Government’s efforts to secure a second resolution faced opposition

from those countries, notably France, Germany and Russia, which believed that the

inspections process could continue. The inspectors reported that Iraqi co‑operation,

while far from perfect, was improving.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

6

19. By early March, the US Administration was not prepared to allow inspections

to continue or give Mr Blair more time to try to achieve support for action. The attempt

to gain support for a second resolution was abandoned.

20. In the Inquiry’s view, the diplomatic options had not at that stage been exhausted.

Military action was therefore not a last resort.

21. In mid‑March, Mr Blair’s determination to stand alongside the US left the UK

with a stark choice. It could act with the US but without the support of the majority

of the Security Council in taking military action if Saddam Hussein did not accept

the US ultimatum giving him 48 hours to leave. Or it could choose not to join US‑led

military action.

22. Led by Mr Blair, the UK Government chose to support military action.

23. Mr Blair asked Parliament to endorse a decision to invade and occupy a sovereign

nation, without the support of a Security Council resolution explicitly authorising the use

of force. Parliament endorsed that choice.

The UK decision to support US military action

24. President Bush decided at the end of 2001 to pursue a policy of regime change

in Iraq.

25. The UK shared the broad objective of finding a way to deal with Saddam Hussein’s

defiance of UN Security Council resolutions and his assumed weapons of mass

destruction (WMD) programmes. However, based on consistent legal advice, the UK

could not share the US objective of regime change. The UK Government therefore set

as its objective the disarmament of Iraq in accordance with the obligations imposed in a

series of Security Council resolutions.

UK policy before 9/11

26. Before the attacks on the US on 11 September 2001 (9/11), the UK was pursuing

a strategy of containment based on a new sanctions regime to improve international

support and incentivise Iraq’s co‑operation, narrowing and deepening the sanctions

regime to focus only on prohibited items and at the same time improving financial

controls to reduce the flow of illicit funds to Saddam Hussein.

27. When UK policy towards Iraq was formally reviewed and agreed by the Ministerial

Committee on Defence and Overseas Policy (DOP) in May 1999, the objectives towards

Iraq were defined as:

“... in the short term, to reduce the threat Saddam poses to the region including

by eliminating his weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programmes; and, in

Executive Summary

7

the longer term, to reintegrate a territorially intact Iraq as a law‑abiding member

of the international community.”1

28. The policy of containment was seen as the “only viable way” to pursue those

objectives. A “policy of trying to topple Saddam would command no useful international

support”. Iraq was unlikely to accept the package immediately but “might be persuaded

to acquiesce eventually”.

29. After prolonged discussion about the way ahead, the UN Security Council adopted

resolution 1284 in December 1999, although China, France and Russia abstained.2

30. The resolution established:

• a new inspectorate, the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection

Commission (UNMOVIC) (which Dr Hans Blix was subsequently appointed

to lead);

• a timetable to identify and agree a work programme; and

• the principle that, if the inspectors reported co‑operation in key areas, that would

lead to the suspension of economic sanctions.3

31. Resolution 1284 described Iraq’s obligations to comply with the disarmament

standards of resolution 687 and other related resolutions as the “governing standard

of Iraqi compliance”; and provided that the Security Council would decide what was

required of Iraq for the implementation of each task and that it should be “clearly defined

and precise”.

32. The resolution was also a deliberate compromise which changed the criterion for

the suspension, and eventual lifting, of sanctions from complete disarmament to tests

which would be based on judgements by UNMOVIC on the progress made in completing

identified tasks.

33. Iraq refused to accept the provisions of resolution 1284, including the re‑admission

of weapons inspectors. Concerns about Iraq’s activities in the absence of inspectors

increased.

34. The US Presidential election in November 2000 prompted a further UK review of the

operation of the containment policy (see Section 1.2). There were concerns about how

long the policy could be sustained and what it could achieve.

35. There were also concerns over both the continued legal basis for operations in the

No‑Fly Zones (NFZs) and the conduct of individual operations.4

1 Joint Memorandum by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs and the Secretary of

State for Defence, 17 May 1999, ‘Iraq Future Strategy’.

2 UN Security Council Press Release, 17 December 1999, Security Council Establishes New Monitoring

Commission For Iraq Adopting Resolution 1284 (1999) By Vote of 11‑0‑4 (SC/6775). 3 UN Security Council, ‘4084th Meeting Friday 17 December 1999’ (S/PV.4084).

4 Letter Goulty to McKane, 20 October 2000, ‘Iraq’.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

8

36. In an Assessment on 1 November, the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) judged

that Saddam Hussein felt “little pressure to negotiate over ... resolution 1284 because

the proceeds of oil smuggling and illicit trade have increased significantly this year, and

more countries are increasing diplomatic contacts and trade with Iraq”.5

37. The JIC also judged:

“Saddam would only contemplate co‑operation with [resolution] 1284, and the return

of inspectors ... if it could be portrayed as a victory. He will not agree to co‑operate

unless:

• there is a UN‑agreed timetable for the lifting of sanctions. Saddam suspects

that the US would not agree to sanctions lift while he remained in power;

• he is able to negotiate with the UN in advance to weaken the inspection

provisions. His ambitions to rebuild Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction

programmes makes him hostile to intrusive inspections or any other constraints

likely to be effective.

“Before accepting 1284, Saddam will try to obtain the abolition of the No‑Fly Zones.

He is also likely to demand that the US should abandon its stated aim to topple the

Iraqi regime.”

38. In November 2000, Mr Blair’s “preferred option” was described as the

implementation of 1284, enabling inspectors to return and sanctions to be suspended.6

39. In December 2000, the British Embassy Washington reported growing pressure

to change course from containment to military action to oust Saddam Hussein,

but no decision to change policy or to begin military planning had been taken by

President Clinton.7

40. The Key Judgements of a JIC Assessment in February 2001 included:

• There was “broad international consensus to maintain the arms embargo

at least as long as Saddam remains in power. Saddam faces no economic

pressure to accept ... [resolution] 1284 because he is successfully

undermining the economic sanctions regime.”

• “Through abuse of the UN Oil‑for‑Food [OFF] programme and smuggling of

oil and other goods” it was estimated that Saddam Hussein would “be able to

appropriate in the region of $1.5bn to $1.8bn in cash and goods in 2001”,

and there was “scope for earning even more”.

5 JIC Assessment, 1 November 2000, ‘Iraq: Prospects for Co‑operation with UNSCR 1284’. 6 Letter Sawers to Cowper‑Coles, 27 November 2000, ‘Iraq’. 7 Letter Barrow to Sawers, 15 December 2000, ‘Iraq’.

Executive Summary

9

• “Iranian interdiction efforts” had “significantly reduced smuggling down

the Gulf”, but Saddam Hussein had “compensated by exploiting land routes

to Turkey and Syria”.

• “Most countries” believed that economic sanctions were “ineffective,

counterproductive and should now be lifted. Without active enforcement,

the economic sanctions regime” would “continue to erode”.8

41. The Assessment also stated:

• Saddam Hussein needed funds “to maintain his military and security apparatus

and secure its loyalty”.

• Despite the availability of funds, Iraq had been slow to comply with UN

recommendations on food allocation. Saddam needed “the Iraqi people

to suffer to underpin his campaign against sanctions”.

• Encouraged by the success of Iraq’s border trade agreement with Turkey,

“front‑line states” were “not enforcing sanctions”.

• There had been a “significant increase in the erosion of sanctions over

the past six months”.

42. When Mr Blair had his first meeting with President Bush at Camp David in late

February 2001, the US and UK agreed on the need for a policy which was more widely

supported in the Middle East region.9

Mr Blair had concluded that public presentation

needed to be improved. He suggested that the approach should be presented as a

“deal” comprising four elements:

• do the right thing by the Iraqi people, with whom we have no quarrel;

• tighten weapons controls on Saddam Hussein;

• retain financial control on Saddam Hussein; and

• retain our ability to strike.

43. The stated position of the UK Government in February 2001 was that containment

had been broadly successful.10

44. During the summer of 2001, the UK had been exploring the way forward with the

US, Russia and France on a draft Security Council resolution to put in place a “smart

sanctions” regime.11 But there was no agreement on the way ahead between the UK, the

US, China, France and Russia, the five Permanent Members of the UN Security Council.

8 JIC Assessment, 14 February 2001, ‘Iraq: Economic Sanctions Eroding’.

9 Letter Sawers to Cowper‑Coles, 24 February 2001, ‘Prime Minister’s Talks with President Bush,

Camp David, 23 February 2001’. 10 House of Commons, Official Report, 26 February 2001, column 620. 11 Minute McKane to Manning, 18 September 2001, ‘Iraq Stocktake’.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

10

45. Mr Blair told the Inquiry that, until 11 September 2001, the UK had a policy of

containment, but sanctions were eroding.12 The policy was “partially successful”,

but it did not mean that Saddam Hussein was “not still developing his [prohibited]

programmes”.

The impact of 9/11

46. The attacks on the US on 11 September 2001 changed perceptions about the

severity and likelihood of the threat from international terrorism. They showed that

attacks intended to cause large‑scale civilian casualties could be mounted anywhere

in the world.

47. In response to that perception of a greater threat, governments felt a responsibility

to act to anticipate and reduce risks before they turned into a threat. That was described

to the Inquiry by a number of witnesses as a change to the “calculus of risk” after 9/11.

48. In the wake of the attacks, Mr Blair declared that the UK would stand “shoulder

to shoulder” with the US to defeat and eradicate international terrorism.13

49. The JIC assessed on 18 September that the attacks on the US had “set a new

benchmark for terrorist atrocity”, and that terrorists seeking comparable impact

might try to use chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear devices.14 Only Islamic

extremists such as those who shared Usama Bin Laden’s agenda had the motivation

to pursue attacks with the deliberate aim of causing maximum casualties.

50. Throughout the autumn of 2001, Mr Blair took an active and leading role in

building a coalition to act against that threat, including military action against Al Qaida

and the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. He also emphasised the potential risk of

terrorists acquiring and using nuclear, biological or chemical weapons, and the

dangers of inaction.

51. In November 2001, the JIC assessed that Iraq had played no role in the 9/11 attacks

on the US and that practical co‑operation between Iraq and Al Qaida was “unlikely”.15

There was no “credible evidence of covert transfers of WMD‑related technology and

expertise to terrorist groups”. It was possible that Iraq might use WMD in terrorist

attacks, but only if the regime was under serious and imminent threat of collapse.

52. The UK continued actively to pursue a strengthened policy of containing Iraq,

through a revised and more targeted sanctions regime and seeking Iraq’s agreement

to the return of inspectors as required by resolution 1284 (1999).

12 Public hearing, 21 January 2011, page 8.

13 The National Archives, 11 September 2001, September 11 attacks: Prime Minister’s statement. 14 JIC Assessment, 18 September 2001, ‘UK Vulnerability to Major Terrorist Attack’.

15 JIC Assessment, 28 November 2001, ‘Iraq after September 11 – The Terrorist Threat’.

Executive Summary

11

53. The adoption on 29 November 2001 of resolution 1382 went some way towards that

objective. But support for economic sanctions was eroding and whether Iraq would ever

agree to re-admit weapons inspectors and allow them to operate without obstruction was

in doubt.

54. Although there was no evidence of links between Iraq and Al Qaida, Mr Blair

encouraged President Bush to address the issue of Iraq in the context of a wider

strategy to confront terrorism after the attacks of 9/11. He sought to prevent precipitate

military action by the US which he considered would undermine the success of the

coalition which had been established for action against international terrorism.

55. President Bush’s remarks16 on 26 November renewed UK concerns that US

attention was turning towards military action in Iraq.

56. Following a discussion with President Bush on 3 December, Mr Blair sent him

a paper on a second phase of the war against terrorism.17

57. On Iraq, Mr Blair suggested a strategy for regime change in Iraq. This would build

over time until the point was reached where “military action could be taken if necessary”,

without losing international support.

58. The strategy was based on the premise that Iraq was a threat which had to be dealt

with, and it had multiple diplomatic strands. It entailed renewed demands for Iraq to

comply with the obligations imposed by the Security Council and for the re‑admission

of weapons inspectors, and a readiness to respond firmly if Saddam Hussein failed

to comply.

59. Mr Blair did not, at that stage, have a ground invasion of Iraq or immediate military

action of any sort in mind. The strategy included mounting covert operations in support

of those “with the ability to topple Saddam”. But Mr Blair did state that, when a rebellion

occurred, the US and UK should “back it militarily”.

60. That was the first step towards a policy of possible intervention in Iraq.

61. A number of issues, including the legal basis for any military action, would need

to be resolved as part of developing the strategy.

62. The UK Government does not appear to have had any knowledge at that stage

that President Bush had asked General Tommy Franks, Commander in Chief,

US Central Command, to review the military options for removing Saddam Hussein,

including options for a conventional ground invasion.

63. Mr Blair also emphasised the threat which Iraq might pose in the future.

That remained a key part of his position in the months that followed.

16 The White House, 26 November 2001, The President Welcomes Aid Workers Rescued from

Afghanistan.

17 Paper [Blair to Bush], 4 December 2001, ‘The War against Terrorism: The Second Phase’.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

12

64. In his annual State of the Union speech on 29 January 2002, President Bush

described the regimes in North Korea and Iran as “sponsors of terrorism”.18 He added

that Iraq had continued to:

“... flaunt its hostility towards America and to support terror ... The Iraqi regime has

plotted to develop anthrax, and nerve gas, and nuclear weapons for over a decade.

This is a regime that has already used poison gas to murder thousands of its own

citizens ... This is a regime that agreed to international inspections – then kicked out

the inspectors. This is a regime that has something to hide from the civilized world.”

65. President Bush stated:

“States like these [North Korea, Iran and Iraq], and their terrorist allies, constitute an

axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world. By seeking weapons of mass

destruction these regimes pose a grave and growing danger.”

66. From late February 2002, Mr Blair and Mr Straw began publicly to argue that Iraq

was a threat which had to be dealt with. Iraq needed to disarm or be disarmed.

67. The urgency and certainty with which the position was stated reflected the

ingrained belief that Saddam Hussein’s regime retained chemical and biological warfare

capabilities, was determined to preserve and if possible enhance its capabilities,

including at some point in the future a nuclear capability, and was pursuing an active

policy of deception and concealment. It also reflected the wider context in which the

policy was being discussed with the US.

68. On 26 February 2002, Sir Richard Dearlove, the Chief of the Secret Intelligence

Service, advised that the US Administration had concluded that containment would

not work, was drawing up plans for a military campaign later in the year, and was

considering presenting Saddam Hussein with an ultimatum for the return of inspectors

while setting the bar “so high that Saddam Hussein would be unable to comply”.19

69. The following day, the JIC assessed that Saddam Hussein feared a US military

attack on the scale of the 1991 military campaign to liberate Kuwait but did not regard

such an attack as inevitable; and that Iraqi opposition groups would not act without

“visible and sustained US military support on the ground”.20

70. At Cabinet on 7 March, Mr Blair and Mr Straw emphasised that no decisions

to launch further military action had been taken and any action taken would be in

accordance with international law.

18 The White House, 29 January 2002, The President’s State of the Union Address. 19 Letter C to Manning, 26 February 2002, ‘US Policy on Iraq’.

20 JIC Assessment, 27 February 2002, ‘Iraq: Saddam Under the Spotlight’.

Executive Summary

13

71. The discussion in Cabinet was couched in terms of Iraq’s need to comply with its

obligations, and future choices by the international community on how to respond to the

threat which Iraq represented.

72. Cabinet endorsed the conclusion that Iraq’s WMD programmes posed a threat to

peace, and endorsed a strategy of engaging closely with the US Government in order to

shape policy and its presentation. It did not discuss how that might be achieved.

73. Mr Blair sought and was given information on a range of issues before his

meeting with President Bush at Crawford on 5 and 6 April. But no formal and agreed

analysis of the issues and options was sought or produced, and there was no collective

consideration of such advice.

74. Mr Straw’s advice of 25 March proposed that the US and UK should seek an

ultimatum to Saddam Hussein to re-admit weapons inspectors.21 That would provide a

route for the UK to align itself with the US without adopting the US objective of regime

change. This reflected advice that regime change would be unlawful.

75. At Crawford, Mr Blair offered President Bush a partnership in dealing urgently

with the threat posed by Saddam Hussein. He proposed that the UK and the US should

pursue a strategy based on an ultimatum calling on Iraq to permit the return of weapons

inspectors or face the consequences.22

76. President Bush agreed to consider the idea but there was no decision until

September 2002.

77. In the subsequent press conference on 6 April, Mr Blair stated that “doing nothing”

was not an option: the threat of WMD was real and had to be dealt with.23 The lesson

of 11 September was to ensure that “groups” were not allowed to develop a capability

they might use.

78. In his memoir, Mr Blair characterised the message that he and President Bush had

delivered to Saddam Hussein as “change the regime attitude on WMD inspections or

face the prospect of changing regime”.24

79. Documents written between April and July 2002 reported that, in the discussion

with President Bush at Crawford, Mr Blair had set out a number of considerations

in relation to the development of policy on Iraq. These were variously described as:

• The UN inspectors needed to be given every chance of success.

• The US should take action within a multilateral framework with international

support, not unilateral action.

21 Minute Straw to Prime Minister, 25 March 2002, ‘Crawford/Iraq’.

22 Letter Manning to McDonald, 8 April 2002, ‘Prime Minister’s Visit to the United States: 5‑7 April’.

23 The White House, 6 April 2002, President Bush, Prime Minister Blair Hold Press Conference. 24 Blair T. A Journey. Hutchinson, 2010.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

14

• A public information campaign should be mounted to explain the nature

of Saddam Hussein’s regime and the threat he posed.

• Any military action would need to be within the framework of international law.

• The military strategy would need to ensure Saddam Hussein could be removed

quickly and successfully.

• A convincing “blueprint” was needed for a post‑Saddam Hussein Iraq which

would be acceptable to both Iraq’s population and its neighbours.

• The US should advance the Middle East Peace Process in order to improve the

chances of gaining broad support in the Middle East for military action against

Iraq; and to pre‑empt accusations of double standards.

• Action should enhance rather than diminish regional stability.

• Success would be needed in Afghanistan to demonstrate the benefits of

regime change.

80. Mr Blair considered that he was seeking to influence US policy by describing the key

elements for a successful strategy to secure international support for any military action

against Iraq.

81. Key Ministers and some of their most senior advisers thought these were

the conditions that would need to be met if the UK was to participate in US‑led

military action.

82. By July, no progress had been made on the ultimatum strategy and Iraq was still

refusing to admit weapons inspectors as required by resolution 1284 (1999).

83. The UK Government was concerned that the US Administration was contemplating

military action in circumstances where it would be very difficult for the UK to participate

in or, conceivably, to support that action.

84. To provide the basis for a discussion with the US, a Cabinet Office paper of 19 July,

‘Iraq: Conditions for Military Action’, identified the conditions which would be necessary

before military action would be justified and the UK could participate in such action.25

85. The Cabinet Office paper stated that Mr Blair had said at Crawford:

“... that the UK would support military action to bring about regime change, provided

that certain conditions were met:

• efforts had been made to construct a coalition/shape public opinion,

• the Israel‑Palestine Crisis was quiescent, and

• the options for action to eliminate Iraq’s WMD through the UN weapons

inspectors had been exhausted.”

25 Paper Cabinet Office, 19 July 2002, ‘Iraq: Conditions for Military Action’.

Executive Summary

15

86. The Cabinet Office paper also identified the need to address the issue of whether

the benefits of military action would outweigh the risks.

87. The potential mismatch between the timetable and work programme for UNMOVIC

stipulated in resolution 1284 (1999) and the US plans for military action was recognised

by officials during the preparation of the Cabinet Office paper.26

88. The issue was not addressed in the final paper submitted to Ministers on 19 July.

27

89. Sir Richard Dearlove reported that he had been told that the US had already taken

a decision on action – “the question was only how and when”; and that he had been told

it intended to set the threshold on weapons inspections so high that Iraq would not be

able to hold up US policy.28

90. Mr Blair’s meeting with Ministerial colleagues and senior officials on 23 July was

not seen by those involved as having taken decisions.29

91. Further advice and background material were commissioned, including on the

possibility of a UN ultimatum to Iraq and the legal basis for action. The record stated:

“We should work on the assumption that the UK would take part in any military

action. But we needed a fuller picture of US planning before we could take any firm

decisions. CDS [the Chief of the Defence Staff, Admiral Sir Michael Boyce] should

tell the US military that we were considering a range of options.”

92. Mr Blair was advised that there would be “formidable obstacles” to securing a new

UN resolution incorporating an ultimatum without convincing evidence of a greatly

increased threat from Iraq.30 A great deal more work would be needed to clarify what the

UK was seeking and how its objective might best be achieved.

93. Mr Blair’s Note to President Bush of 28 July sought to persuade President Bush to

use the UN to build a coalition for action by seeking a partnership between the UK and

the US and setting out a framework for action.31

94. The Note began:

“I will be with you, whatever. But this is the moment to assess bluntly the difficulties.

The planning on this and the strategy are the toughest yet. This is not Kosovo.

This is not Afghanistan. It is not even the Gulf War.

26 Paper [Draft] Cabinet Office, ‘Iraq: Conditions for Military Action’ attached to Minute McKane to Bowen,

16 July 2002, ‘Iraq’.

27 Paper Cabinet Office, 19 July 2002, ‘Iraq: Conditions for Military Action’. 28 Report, 22 July 2002, ‘Iraq [C’s account of discussions with Dr Rice]’. 29 Minute Rycroft to Manning, 23 July 2002, ‘Iraq: Prime Minister’s Meeting, 23 July’.

30 Letter McDonald to Rycroft, 26 July 2002, ‘Iraq: Ultimatum’ attaching Paper ‘Elements which might

be incorporated in an SCR embodying an ultimatum to Iraq’. 31 Note Blair [to Bush], 28 July 2002, ‘Note on Iraq’.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

16

“The military part of this is hazardous but I will concentrate mainly on the political

context for success.”

95. Mr Blair stated that getting rid of Saddam Hussein was:

“... the right thing to do. He is a potential threat. He could be contained.

But containment ... is always risky. His departure would free up the region.

And his regime is ... brutal and inhumane ...”

96. Mr Blair told President Bush that the UN was the simplest way to encapsulate a

“casus belli” in some defining way, with an ultimatum to Iraq once military forces started

to build up in October. That might be backed by a UN resolution.

97. Mr Blair thought it unlikely that Saddam Hussein intended to allow inspectors to

return. If he did, the JIC had advised that Iraq would obstruct the work of the inspectors.

That could result in a material breach of the obligations imposed by the UN.

98. A workable military plan to ensure the collapse of the regime would be required.

99. The Note reflected Mr Blair’s own views. The proposals had not been discussed

or agreed with his colleagues.

Decision to take the UN route

100. Sir David Manning, Mr Blair’s Foreign Policy Adviser, told President Bush that it

would be impossible for the UK to take part in any action against Iraq unless it went

through the UN.

101. When Mr Blair spoke to President Bush on 31 July the “central issue of a casus

belli” and the need for further work on the optimal route to achieve that was discussed.32

Mr Blair said that he wanted to explore whether the UN was the right route to set an

ultimatum or whether it would be an obstacle.

102. In late August, the FCO proposed a strategy of coercion, using a UN resolution

to issue an ultimatum to Iraq to admit the weapons inspectors and disarm. The UK

was seeking a commitment from the Security Council to take action in the event that

Saddam Hussein refused or subsequently obstructed the inspectors.

103. Reflecting the level of public debate and concern, Mr Blair decided in early

September that an explanation of why action was needed to deal with Iraq should

be published.

32 Rycroft to McDonald, 31 July 2002, ‘Iraq: Prime Minister’s Phone Call with President Bush, 31 July’.

Executive Summary

17

104. In his press conference at Sedgefield on 3 September, Mr Blair indicated that time

and patience were running out and that there were difficulties with the existing policy of

containment.33 He also announced the publication of the Iraq dossier, stating that:

“... people will see that there is no doubt at all the United Nations resolutions that

Saddam is in breach of are there for a purpose. He [Saddam Hussein] is without any

question, still trying to develop that chemical, biological, potentially nuclear capability

and to allow him to do so without any let or hindrance, just to say, we [sic] can carry

on and do it, I think would be irresponsible.”

105. President Bush decided in the meeting of the National Security Council on

7 September to take the issue of Iraq back to the UN.

106. The UK was a key ally whose support was highly desirable for the US. The US

Administration had been left in no doubt that the UK Government needed the issue

of Iraq to be taken back to the Security Council before it would be able to participate

in military action in Iraq.

107. The objective of the subsequent discussions between President Bush and Mr Blair

at Camp David was, as Mr Blair stated in the press conference before the discussions,

to work out the strategy.34

108. Mr Blair told President Bush that he was in no doubt about the need to deal with

Saddam Hussein.35

109. Although at that stage no decision had been taken on which military package might

be offered to the US for planning purposes, Mr Blair also told President Bush that, if it

came to war, the UK would take a significant military role.

110. In his speech to the General Assembly on 12 September, President Bush set out

his view of the “grave and gathering danger” posed by Saddam Hussein and challenged

the UN to act to address Iraq’s failure to meet the obligations imposed by the Security

Council since 1990.36 He made clear that, if Iraq defied the UN, the world must hold

Iraq to account and the US would “work with the UN Security Council for the necessary

resolutions”. But the US would not stand by and do nothing in the face of the threat.

111. Statements made by China, France and Russia in the General Assembly debate

after President Bush’s speech highlighted the different positions of the five Permanent

Members of the Security Council, in particular about the role of the Council in deciding

whether military action was justified.

33 The National Archives, 3 September 2002, PM press conference [at Sedgefield]. 34 The White House, 7 September 2002, President Bush, Prime Minister Blair Discuss Keeping the Peace. 35 Minute Manning to Prime Minister, 8 September 2002, ‘Your Visit to Camp David on 7 September:

Conversation with President Bush’.

36 The White House, 12 September 2002, President’s Remarks to the United Nations General Assembly.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

18

112. The Government dossier on Iraq was published on 24 September.37 It was

designed to “make the case” and secure Parliamentary (and public) support for the

Government’s policy that action was urgently required to secure Iraq’s disarmament.

113. In his statement to Parliament on 24 September and in his answers to subsequent

questions, Mr Blair presented Iraq’s past, current and potential future capabilities as

evidence of the severity of the potential threat from Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction.

He said that at some point in the future that threat would become a reality.

38

114. Mr Blair wrote his statement to the House of Commons himself and chose the

arguments to make clear his perception of the threat and why he believed that there

was an “overwhelming” case for action to disarm Iraq.

115. Addressing the question of why Saddam Hussein had decided in mid‑September,

but not before, to admit the weapons inspectors, Mr Blair stated that the answer was in

the dossier, and it was because:

“... his chemical, biological and nuclear programme is not an historic left‑over from

1998. The inspectors are not needed to clean up the old remains. His weapons

of mass destruction programme is active detailed and growing. The policy of

containment is not working. The weapons of mass destruction programme is not

shut down; it is up and running now.”

116. Mr Blair posed, and addressed, three questions: “Why Saddam?”; “Why now?”;

and “Why should Britain care?”

117. On the question “Why Saddam?”, Mr Blair said that two things about Saddam

Hussein stood out: “He had used these weapons in Iraq” and thousands had died, and

he had used them during the war with Iran “in which one million people died”; and the

regime had “no moderate elements to appeal to”.

118. On the question “Why now?”, Mr Blair stated:

“I agree I cannot say that this month or next, even this year or next, Saddam will

use his weapons. But I can say that if the international community, having made

the call for his disarmament, now, at this moment, at the point of decision, shrugs

its shoulders and walks away, he will draw the conclusion dictators faced with a

weakening will always draw: that the international community will talk but not act,

will use diplomacy but not force. We know, again from our history, that diplomacy

not backed by the threat of force has never worked with dictators and never will.”

37 Iraq’s Weapons of Mass Destruction. The Assessment of the British Government, 24 September 2002. 38 House of Commons, Official Report, 24 September 2002, columns 1‑23.

Executive Summary

19

Negotiation of resolution 1441

119. There were significant differences between the US and UK positions, and between

them and China, France and Russia about the substance of the strategy to be adopted,

including the role of the Security Council in determining whether peaceful means had

been exhausted and the use of force to secure disarmament was justified.

120. Those differences resulted in difficult negotiations over more than eight weeks

before the unanimous adoption of resolution 1441 on 8 November 2002.

121. When President Bush made his speech on 12 September, the US and UK had

agreed the broad approach, but not the substance of the proposals to be put to the

UN Security Council or the tactics.

122. Dr Naji Sabri, the Iraqi Foreign Minister, wrote to Mr Kofi Annan, the

UN Secretary‑General, on 16 September to inform him that, following the series of talks

between Iraq and the UN in New York and Vienna between March and July 2002 and the

latest round in New York on 14 and 15 September, Iraq had decided “to allow the return

of United Nations inspectors to Iraq without conditions”.39

123. The US and UK immediately expressed scepticism. They had agreed that the

provisions of resolution 1284 (1999) were no longer sufficient to secure the disarmament

of Iraq and a strengthened inspections regime would be required.

124. A new resolution would be needed both to maintain the pressure on Iraq and to

define a more intrusive inspections regime allowing the inspectors unconditional and

unrestricted access to all Iraqi facilities.

125. The UK’s stated objective for the negotiation of resolution 1441 was to

give Saddam Hussein “one final chance to comply” with his obligations to disarm.

The UK initially formulated the objective in terms of:

• a resolution setting out an ultimatum to Iraq to re-admit the UN weapons

inspectors and to disarm in accordance with its obligations; and

• a threat to resort to the use of force to secure disarmament if Iraq failed

to comply.40

126. Lord Goldsmith, the Attorney General, informed Mr Blair on 22 October that,

although he would not be able to give a final view until the resolution was adopted, the

draft of the resolution of 19 October would not on its own authorise military action.41

39 UN Security Council, 16 September 2002, ‘Letter dated 16 September from the Minister of Foreign

Affairs of Iraq addressed to the Secretary-General’, attached to ‘Letter dated 16 September from the

Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council’ (S/2002/1034). 40 Minute Straw to Prime Minister, 14 September 2002, ‘Iraq: Pursuing the UN Route’.

41 Minute Adams to Attorney General, 22 October 2002, ‘Iraq: Meeting with the Prime Minister, 22 October’

attaching Briefing, ‘Lines to take’.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

20

127. Mr Blair decided on 31 October to offer significant forces for ground operations

to the US for planning purposes.42

128. During the negotiations, France and Russia made clear their opposition to the use

of force, without firm evidence of a further material breach and a further decision in the

Security Council.

129. The UK was successful in changing some aspects of the US position during the

negotiations, in particular ensuring that the Security Council resolution was based on

the disarmament of Iraq rather than wider issues as originally proposed by the US.

130. To secure consensus in the Security Council despite the different positions of the

US and France and Russia (described by Sir Jeremy Greenstock, the UK Permanent

Representative to the UN in New York, as “irreconcilable”), resolution 1441 was a

compromise containing drafting “fixes”. That created deliberate ambiguities on a number

of key issues including:

• the level of non‑compliance with resolution 1441 which would constitute

a material breach;

• by whom that determination would be made; and

• whether there would be a second resolution explicitly authorising the use

of force.

131. As the Explanations of Vote demonstrated, there were significant differences

between the positions of the members of the Security Council about the circumstances

and timing of recourse to military action. There were also differences about whether

Member States should be entitled to report Iraqi non‑compliance to the Council.

132. Mr Blair, Mr Straw and other senior UK participants in the negotiation of resolution

1441 envisaged that, in the event of a material breach of Iraq’s obligations, a second

resolution determining that a breach existed and authorising the use of force was likely

to be tabled in the Security Council.

133. Iraq announced on 13 November that it would comply with resolution 1441.43

134. Iraq also restated its position that it had neither produced nor was in possession

of weapons of mass destruction since the inspectors left in December 1998. It explicitly

challenged the UK statement on 8 November that Iraq had “decided to keep possession”

of its WMD.

42 Letter Wechsberg to Watkins, 31 October 2002, ‘Iraq: Military Options’.

43 UN Security Council, 13 November 2002, ‘Letter dated 13 November 2002 from the Minister for Foreign

Affairs of Iraq addressed to the Secretary-General’ (S/2002/1242).

Executive Summary

21

The prospect of military action

135. Following Iraq’s submission of the declaration on its chemical, biological, nuclear

and ballistic missile programmes to the UN on 7 December, and before the inspectors

had properly begun their task, the US concluded that Saddam Hussein was not going

to take the final opportunity offered by resolution 1441 to comply with his obligations.

136. Mr Blair was advised on 11 December that there was impatience in the US

Administration and it was looking at military action as early as mid‑February 2003.44

137. Mr Blair told President Bush on 16 December that the Iraqi declaration was

“patently false”.45 He was “cautiously optimistic” that the inspectors would find proof.

138. In a statement issued on 18 December, Mr Straw said that Saddam Hussein had

decided to continue the pretence that Iraq had no WMD programme. If he persisted

“in this obvious falsehood” it would become clear that he had “rejected the pathway

to peace”.46

139. The JIC’s initial Assessment of the Iraqi declaration on 18 December stated

that there had been “No serious attempt” to answer any of the unresolved questions

highlighted by the UN Special Commission (UNSCOM) or to refute any of the points

made in the UK dossier on Iraq’s WMD programme.47

140. President Bush is reported to have told a meeting of the US National Security

Council on 18 December 2002, at which the US response to Iraq’s declaration

was discussed, that the point of the 7 December declaration was to test whether

Saddam Hussein would accept the “final opportunity” for peace offered by the Security

Council.48 He had summed up the discussion by stating:

“We’ve got what we need now, to show America that Saddam won’t disarm himself.”

141. Mr Colin Powell, the US Secretary of State, stated on 19 December that Iraq was

“well on its way to losing its last chance”, and that there was a “practical limit” to how

long the inspectors could be given to complete their work.49

142. Mr Straw told Secretary Powell on 30 December that the US and UK should

develop a clear “plan B” postponing military action on the basis that inspections plus

the threat of force were containing Saddam Hussein.50

44 Minute Manning to Prime Minister, 11 December 2002, ‘Iraq’.

45 Letter Rycroft to McDonald, 16 December 2002, ‘Prime Minister’s Telephone Call with President Bush,

16 December’. 46 The National Archives, 18 December 2002, Statement by Foreign Secretary on Iraq Declaration. 47 JIC Assessment, 18 December 2002, ‘An Initial Assessment of Iraq’s WMD Declaration’. 48 Feith DJ. War and Decision: Inside the Pentagon at the Dawn of the War on Terrorism. HarperCollins,

2008.

49 US Department of State Press Release, Press Conference Secretary of State Colin L Powell,

Washington, 19 December 2002. 50 Letter Straw to Manning, 30 December 2002, ‘Iraq: Conversation with Colin Powell, 30 December’.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

22

143. In early 2003, Mr Straw still thought a peaceful solution was more likely than

military action. Mr Straw advised Mr Blair on 3 January that he had concluded that, in

the potential absence of a “smoking gun”, there was a need to consider a “Plan B”.51 The

UK should emphasise to the US that the preferred strategy was peaceful disarmament.

144. Mr Blair took a different view. By the time he returned to the office on 4 January

2003, he had concluded that the “likelihood was war” and, if conflict could not be

avoided, the right thing to do was fully to support the US.52 He was focused on the

need to establish evidence of an Iraqi breach, to persuade opinion of the case for

action and to finalise the strategy with President Bush at the end of January.

145. The UK objectives were published in a Written Ministerial Statement by Mr Straw

on 7 January.53 The “prime objective” was:

“... to rid Iraq of its weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and their associated

programmes and means of delivery, including prohibited ballistic missiles ... as set

out in UNSCRs [UN Security Council resolutions]. This would reduce Iraq’s ability

to threaten its neighbours and the region, and prevent Iraq using WMD against its

own people. UNSCRs also require Iraq to renounce terrorism, and return captured

Kuwaitis and property taken from Kuwait.”

146. Lord Goldsmith gave Mr Blair his draft advice on 14 January that resolution 1441

would not by itself authorise the use of military force.54

147. Mr Blair agreed on 17 January to deploy a UK division with three combat brigades

for possible operations in southern Iraq.55

148. There was no collective discussion of the decision by senior Ministers.

149. In January 2003, there was a clear divergence between the UK and US

Government positions over the timetable for military action, and the UK became

increasingly concerned that US impatience with the inspections process would lead

to a decision to take unilateral military action in the absence of support for such action

in the Security Council.

150. On 23 January, Mr Blair was advised that the US military would be ready for action

in mid‑February.56

151. In a Note to President Bush on 24 January, Mr Blair wrote that the arguments

for proceeding with a second Security Council resolution, “or at the very least a

51 Minute Straw to Prime Minister, 3 January 2003, ‘Iraq - Plan B’. 52 Note Blair [to No.10 officials], 4 January 2003, [extract ‘Iraq’]. 53 House of Commons, Official Report, 7 January 2003, columns 4‑6WS. 54 Minute [Draft] [Goldsmith to Prime Minister], 14 January 2003, ‘Iraq: Interpretation of Resolution 1441’.

55 Letter Manning to Watkins, 17 January 2003, ‘Iraq: UK Land Contribution’.

56 Letter PS/C to Manning, 23 January 2003, [untitled].

Executive Summary

23

clear statement” from Dr Blix which allowed the US and UK to argue that a failure

to pass a second resolution was in breach of the spirit of 1441, remained in his view,

overwhelming; and that inspectors should be given until the end of March or early April

to carry out their task.57

152. Mr Blair suggested that, in the absence of a “smoking gun”, Dr Blix would be able

to harden up his findings on the basis of a pattern of non‑co‑operation from Iraq and that

that would be sufficient for support for military action in the Security Council.

153. The US and UK should seek to persuade others, including Dr Blix, that that was

the “true view” of resolution 1441.

154. Mr Blair used an interview on Breakfast with Frost on 26 January to set out the

position that the inspections should be given sufficient time to determine whether or

not Saddam Hussein was co‑operating fully.58 If he was not, that would be a sufficient

reason for military action. A find of WMD was not required.

155. Mr Blair’s proposed approach to his meeting with President Bush was discussed

in a meeting of Ministers before Cabinet on 30 January and then discussed in general

terms in Cabinet itself.

156. In a Note prepared before his meeting with President Bush on 31 January, Mr Blair

proposed seeking a UN resolution on 5 March followed by an attempt to “mobilise Arab

opinion to try to force Saddam out” before military action on 15 March.59

157. When Mr Blair met President Bush on 31 January, it was clear that the window of

opportunity before the US took military action would be very short. The military campaign

could begin “around 10 March”.60

158. President Bush agreed to seek a second resolution to help Mr Blair, but there were

major reservations within the US Administration about the wisdom of that approach.

159. Mr Blair confirmed that he was “solidly with the President and ready to do whatever

it took to disarm Saddam” Hussein.

160. Reporting on his visit to Washington, Mr Blair told Parliament on 3 February 2003

that Saddam Hussein was not co‑operating as required by resolution 1441 and, if that

continued, a second resolution should be passed to confirm such a material breach.61

161. Mr Blair continued to set the need for action against Iraq in the context of the need

to be seen to enforce the will of the UN and to deter future threats.

57 Letter Manning to Rice, 24 January 2003, [untitled], attaching Note [Blair to Bush], [undated], ‘Note’.

58 BBC News, 26 January 2003, Breakfast with Frost. 59 Note [Blair to Bush], [undated], ‘Countdown’. 60 Letter Manning to McDonald, 31 January 2003, ‘Iraq: Prime Minister’s Conversation with President Bush

on 31 January’.

61 House of Commons, Official Report, 3 February 2003, columns 21‑38.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

24

The gap between the Permanent Members of the Security Council

widens

162. In their reports to the Security Council on 14 February:

• Dr Blix reported that UNMOVIC had not found any weapons of mass destruction

and the items that were not accounted for might not exist, but Iraq needed to

provide the evidence to answer the questions, not belittle them.

• Dr Mohamed ElBaradei, Director General of the International Atomic Energy

Agency (IAEA), reported that the IAEA had found no evidence of ongoing

prohibited nuclear or nuclear‑related activities in Iraq although a number

of issues were still under investigation.62

163. In the subsequent debate, members of the Security Council voiced widely

divergent views.

164. Mr Annan concluded that there were real differences on strategy and timing in

the Security Council. Iraq’s non‑co‑operation was insufficient to bring members to agree

that war was justified; they would only move if they came to their own judgement that

inspections were pointless.63

165. On 19 February, Mr Blair sent President Bush a six‑page Note. He proposed

focusing on the absence of full co‑operation and a “simple” resolution stating that Iraq

had failed to take the final opportunity, with a side statement defining tough tests of

co‑operation and a vote on 14 March to provide a deadline for action.64

166. President Bush and Mr Blair agreed to introduce a draft resolution at the UN the

following week but its terms were subject to further discussion.65

167. On 20 February, Mr Blair told Dr Blix that he wanted to offer the US an alternative

strategy which included a deadline and tests for compliance.66 He did not think Saddam

Hussein would co‑operate but he would try to get Dr Blix as much time as possible. Iraq

could have signalled a change of heart in the December declaration. The Americans did

not think that Saddam was going to co‑operate: “Nor did he. But we needed to keep the

international community together.”

168. Dr Blix stated that full co‑operation was a nebulous concept; and a deadline of

15 April would be too early. Dr Blix commented that “perhaps there was not much WMD

in Iraq after all”. Mr Blair responded that “even German and French intelligence were

sure that there was WMD in Iraq”. Dr Blix said they seemed “unsure” about “mobile BW

62 UN Security Council, ‘4707th Meeting Friday 14 February 2003’ (S/PV.4707).

63 Telegram 268 UKMIS New York to FCO London, 15 February 2003, ‘Foreign Secretary’s Meeting with

the UN Secretary‑General: 14 February’.

64 Letter Manning to Rice, 19 February 2003, ‘Iraq’ attaching Note [Blair to Bush], [undated], ‘Note’. 65 Letter Rycroft to McDonald, 19 February 2003, ‘Iraq and MEPP: Prime Minister’s Telephone

Conversation with Bush, 19 February’.

66 Letter Cannon to Owen, 20 February 2003, ‘Iraq: Prime Minister’s Conversation with Blix’.

Executive Summary

25

production facilities”: “It would be paradoxical and absurd if 250,000 men were to invade

Iraq and find very little.”

169. Mr Blair responded that “our intelligence was clear that Saddam had reconstituted

his WMD programme”.

170. On 24 February, the UK, US and Spain tabled a draft resolution stating that Iraq

had failed to take the final opportunity offered by resolution 1441 and that the Security

Council had decided to remain seized of the matter.67 The draft failed to attract support.

171. France, Germany and Russia responded by tabling a memorandum, building on

their tripartite declaration of 10 February, stating that “full and effective disarmament”

remained “the imperative objective of the international community”.68 That “should be

achieved peacefully through the inspection regime”. The “conditions for using force” had

“not been fulfilled”. The Security Council “must step up its efforts to give a real chance

to the peaceful settlement of the crisis”.

172. On 25 February, Mr Blair told the House of Commons that the intelligence was

“clear” that Saddam Hussein continued “to believe that his weapons of mass destruction

programme is essential both for internal repression and for external aggression”.69

It was also “essential to his regional power”. “Prior to the inspectors coming back in”,

Saddam Hussein “was engaged in a systematic exercise in concealment of those

weapons”. The inspectors had reported some co‑operation on process, but had

“denied progress on substance”.

173. The House of Commons was asked on 26 February to reaffirm its endorsement of

resolution 1441, support the Government’s continuing efforts to disarm Iraq, and to call

upon Iraq to recognise that this was its final opportunity to comply with its obligations.70

174. The Government motion was approved by 434 votes to 124; 199 MPs voted for

an amendment which invited the House to “find the case for military action against Iraq

as yet unproven”.71

175. In a speech on 26 February, President Bush stated that the safety of the American

people depended on ending the direct and growing threat from Iraq.72

176. President Bush also set out his hopes for the future of Iraq.

67 Telegram 302 UKMIS New York to FCO London, 25 February 2003, ‘Iraq: Tabling of US/UK/Spanish

Draft Resolution: Draft Resolution’.

68 UN Security Council, 24 February 2003, ‘Letter dated 24 February 2003 from the Permanent

Representatives of France, Germany and the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the

President of the Security Council’ (S/2003/214).

69 House of Commons, Official Report, 25 February 2003, columns 123‑126. 70 House of Commons, Official Report, 26 February 2003, column 265. 71 House of Commons, Official Report, 26 February 2003, columns 367‑371. 72 The White House, 26 February 2003, President discusses the future of Iraq.

The Report of the Iraq Inquiry

26

177. Reporting discussions in New York on 26 February, Sir Jeremy Greenstock wrote

that there was “a general antipathy to having now to take decisions on this issue, and

a wariness about what our underlying motives are behind the resolution”.73 Sir Jeremy

concluded that the US was focused on preserving its room for manoeuvre while he

was “concentrating on trying to win votes”. It was the “middle ground” that mattered.

Mexico and Chile were the “pivotal sceptics”.

178. Lord Goldsmith told No.10 officials on 27 February that the safest legal course for

future military action would be to secure a further Security Council resolution.74 He had,

however, reached the view that a “reasonable case” could be made that resolution 1441

was capable of reviving the authorisation to use force in resolution 678 (1990) without a

further resolution, if there were strong factual grounds for concluding that Iraq had failed

to take the final opportunity offered by resolution 1441.

179. Lord Goldsmith advised that, to avoid undermining the case for reliance on

resolution 1441, it would be important to avoid giving any impression that the UK

believed a second resolution was legally required.

180. Informal consultations in the Security Council on 27 February showed there was

little support for the UK/US/Spanish draft resolution.75

181. An Arab League Summit on 1 March concluded that the crisis in Iraq must be

resolved by peaceful means and in the framework of international legitimacy.

76

182. Following his visit to Mexico, Sir David Manning concluded that Mexican support

for a second resolution was “not impossible, but would not be easy and would almost

certainly require some movement”.77

183. During Sir David’s visit to Chile, President Ricardo Lagos repeated his concerns,

including the difficulty of securing nine votes or winning the presentational battle

without further clarification of Iraq’s non‑compliance. He also suggested identifying

benchmarks.78

184. Mr Blair wrote in his memoir that, during February, “despite his best endeavours”,

divisions in the Security Council had grown not reduced; and that the “dynamics of

disagreement” were producing new alliances.79 France, Germany and Russia were

moving to create an alternative pole of power and influence.

73 Telegram 314 UKMIS New York to FCO London, 27 February 2003, ‘Iraq: 26 February’.

74 Minute Brummell, 27 February 2003, ‘Iraq: Attorney General’s Meeting at No. 10 on 27th February

2003’.

75 Telegram 318 UKMIS New York to FCO London, 28 February 2003, ‘Iraq: 27 February Consultations

and Missiles’.

76 Telegram 68 Cairo to FCO London, 2 March 2003, ‘Arab League Summit: Final Communique’.

77 Telegram 1 Mexico City to Cabinet Office, 1 March 2003, ‘Iraq: Mexico’.

78 Telegram 34 Santiago to FCO London, 2 March 2003, ‘Chile/Iraq: Visit by Manning and Scarlett’.

79 Blair T. A Journey. Hutchinson, 2010.

Executive Summary

27

185. Mr Blair thought that was “highly damaging” but “inevitable”: “They felt as strongly

as I did; and they weren’t prepared to indulge the US, as they saw it.”

186. Mr Blair concluded that for moral and strategic reasons the UK should be with

the US and that:

“... [W]e should make a last ditch attempt for a peaceful solution. First to make

the moral case for removing Saddam ... Second, to try one more time to reunite

the international community behind a clear base for action in the event of a

continuing breach.”

187. On 3 March, Mr Blair proposed an approach focused on setting a deadline of

17 March for Iraq to disclose evidence relating to the destruction of prohibited items

and permit interviews; and an amnesty if Saddam Hussein left Iraq by 21 March.80

188. Mr Straw told Secretary Powell that the level of support in the UK for military action

without a second resolution was palpably “very low”. In that circumstance, even if a

majority in the Security Council had voted for the resolution with only France exercising

its veto, he was “increasingly pessimistic” about support within the Labour Party for

military action.81 The debate in the UK was:

“... significantly defined by the tone of the debate in Washington and particularly

remarks made by the President and others to the right of him, which suggested that

the US would go to war whatever and was not bothered about a second resolution

one way or another.”

189. Following a discussion with Mr Blair, Mr Straw told Secretary Powell that Mr Blair:

“... was concerned that, having shifted world (and British) public opinion over the